Breakthrough 2026 guide to SMR project finance for AI data centers. Learn the capital stack, policy shifts, and risks investors must price.

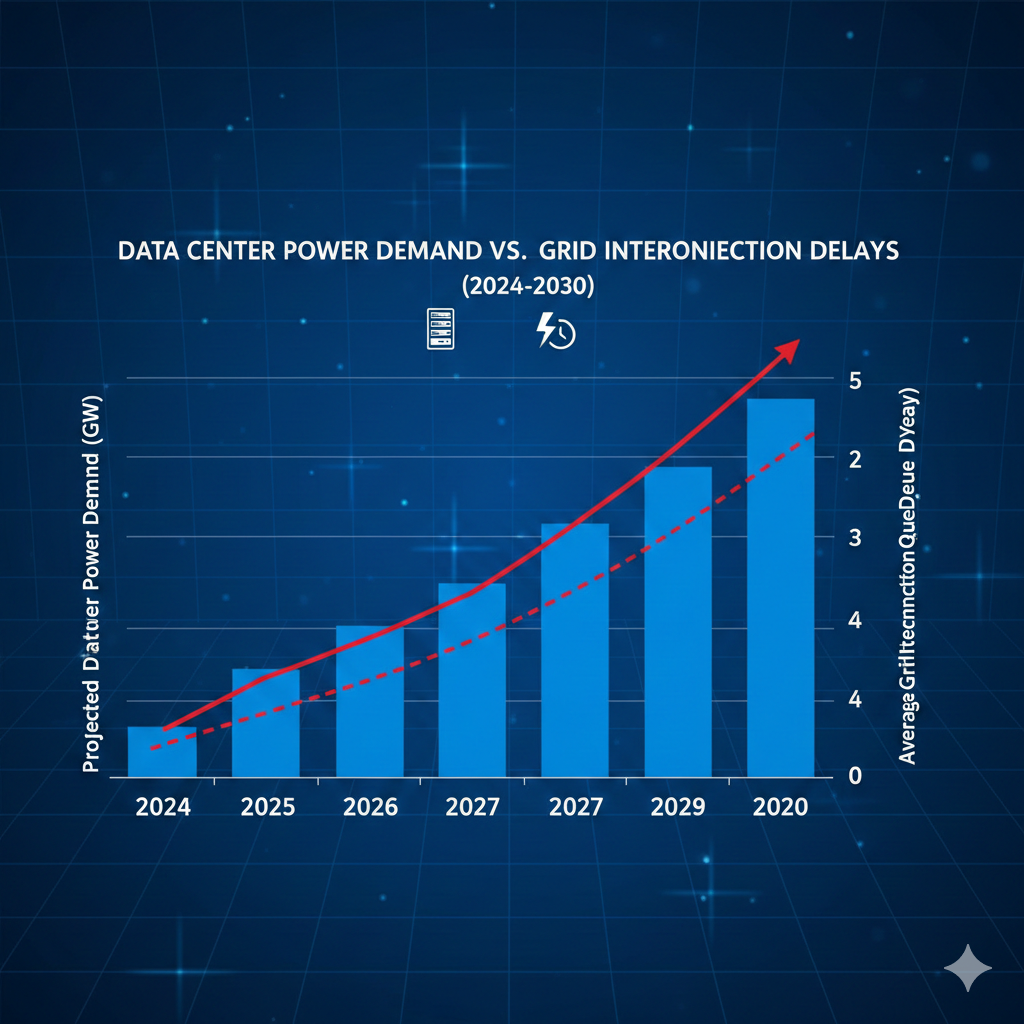

The 2026 setup: AI load meets a power wall

In late 2025, a new sentence keeps popping up in boardrooms. “Power is the new silicon.” It sounds dramatic. It is also painfully practical.

AI data centers are no longer a side bet. They are becoming the core infrastructure of modern business. That shift changes everything about electricity. It turns power from a utility line item into a strategic constraint. Consequently, the investment world is scanning for “clean firm power” that can run all day, in every season, without begging the weather.

Wind and solar still matter. They are fast to build. They can be cheap at the margin. However, they do not behave like a dependable engine by themselves. Storage helps, but the durations add up fast. Meanwhile, transmission queues and interconnection delays are forcing large buyers to think years ahead.

That is the emotional spark behind direct nuclear power and small modular reactors, or SMRs. The pitch is bold. It is also simple. Build a compact nuclear plant. Lock in long-term offtake. Use the steady output to anchor a power-hungry data campus.

This narrative is not theory anymore. Big tech has started signing nuclear deals and SMR framework agreements. Constellation’s announcement of a major PPA with Microsoft tied to restoring Three Mile Island Unit 1 was a loud signal that hyperscalers will sign for long-duration nuclear output when the strategic value is high. (Constellation) Amazon has also publicized SMR agreements as part of its energy strategy. (About Amazon) Google, for its part, announced an agreement with Kairos Power to buy power from multiple SMRs, positioning it as a first-of-its-kind corporate deal in this category. (blog.google)

From an investor lens, the 2026 question is not “Is nuclear back?” The sharper question is: can nuclear be financed like infrastructure again, with a bankable structure, credible counterparties, and disciplined risk allocation?

Why the “energy security” frame is beating the old language

A few years ago, much of the clean-energy conversation was framed as ESG and carbon goals. Entering 2026, the tone is shifting toward reliability, sovereignty, and resilience. The reason is not ideological. It is operational.

AI services cannot pause when the sun sets. Cloud outages are reputational disasters. So the buyer’s emotion is urgency. The buyer’s requirement is firmness. That is why nuclear is rebranding in real time as an “energy security asset,” not just a “clean asset.”

Additionally, governments are also leaning into this shift. In the United States, the ADVANCE Act of 2024 directs the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to take several actions tied to new reactor and fuel licensing, while keeping safety central. That kind of signal matters when you are underwriting multi-year development risk. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission)

The “Bill Gates” hook, and why it matters for finance

Bill Gates is not just a celebrity name in this story. His involvement points to a deeper truth: advanced nuclear projects need patient capital and credibility.

TerraPower’s Natrium project has been moving through tangible milestones, including NRC-facing steps. The NRC’s own project page lists TerraPower’s construction permit application submission date. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) TerraPower has also communicated a target for its NRC timeline into 2026. (TerraPower) Whether a specific project hits each milestone is not guaranteed. Still, visible regulatory progression is exactly what lenders and infrastructure allocators look for when they decide if something is “financeable” versus merely exciting.

[YouTube Video]: Big Tech’s nuclear push to power AI, explained in plain terms. This is useful here because it frames the demand shock that is driving the financing conversation into 2026.

Why SMRs are suddenly investable, even if they are still hard

SMRs sit in a strange place entering 2026. The promise is powerful. The execution is demanding. That mix creates opportunity, but only for investors who price reality.

The core SMR promise is modularity. Smaller units should mean lower single-project risk, faster learning cycles, and repeatable supply chains. That is the “breakthrough” story. Yet nuclear has a long memory. Cost overruns and schedule slips are not distant history. They are the caution tape wrapped around every model.

So what changed?

First, the buyer changed. Hyperscalers are unusually attractive offtakers. They have scale. They have credit strength. They can sign long-term agreements. They also have a direct business reason to pay for reliability.

Second, the policy temperature warmed. When licensing is slow, financing becomes punitive. When licensing becomes more predictable, capital costs can fall. The ADVANCE Act is one example of a policy push aimed at making advanced reactor licensing more workable. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission)

Third, the market structure is evolving. We are seeing more creativity in offtake and risk-sharing. Corporate PPAs, utility partnerships, and hybrid structures are becoming the serious path.

Corporate demand signals you can underwrite

The most persuasive indicator for 2026 is not a brochure. It is signed paper.

Google’s agreement with Kairos Power, framed as a purchase from multiple SMRs, is important as a precedent because it demonstrates that a buyer with sophisticated procurement teams is willing to do the legal and commercial work early. (blog.google) Amazon’s SMR announcements matter for the same reason: they signal that the biggest infrastructure buyers are preparing for a world where “always-on” power is scarce. (About Amazon)

That said, none of these headlines magically deletes nuclear risk. They simply change the financing conversation from “no way” to “show me the structure.”

The real product being sold: certainty

In 2026, the product that nuclear sells to AI is not just kilowatt-hours. It is certainty.

Certainty has a price. It also has a financing value. The more predictable the revenue, the more debt a project can carry, and the lower the weighted cost of capital can become. Consequently, the battle becomes contractual. Who takes what risk, and how is it paid?

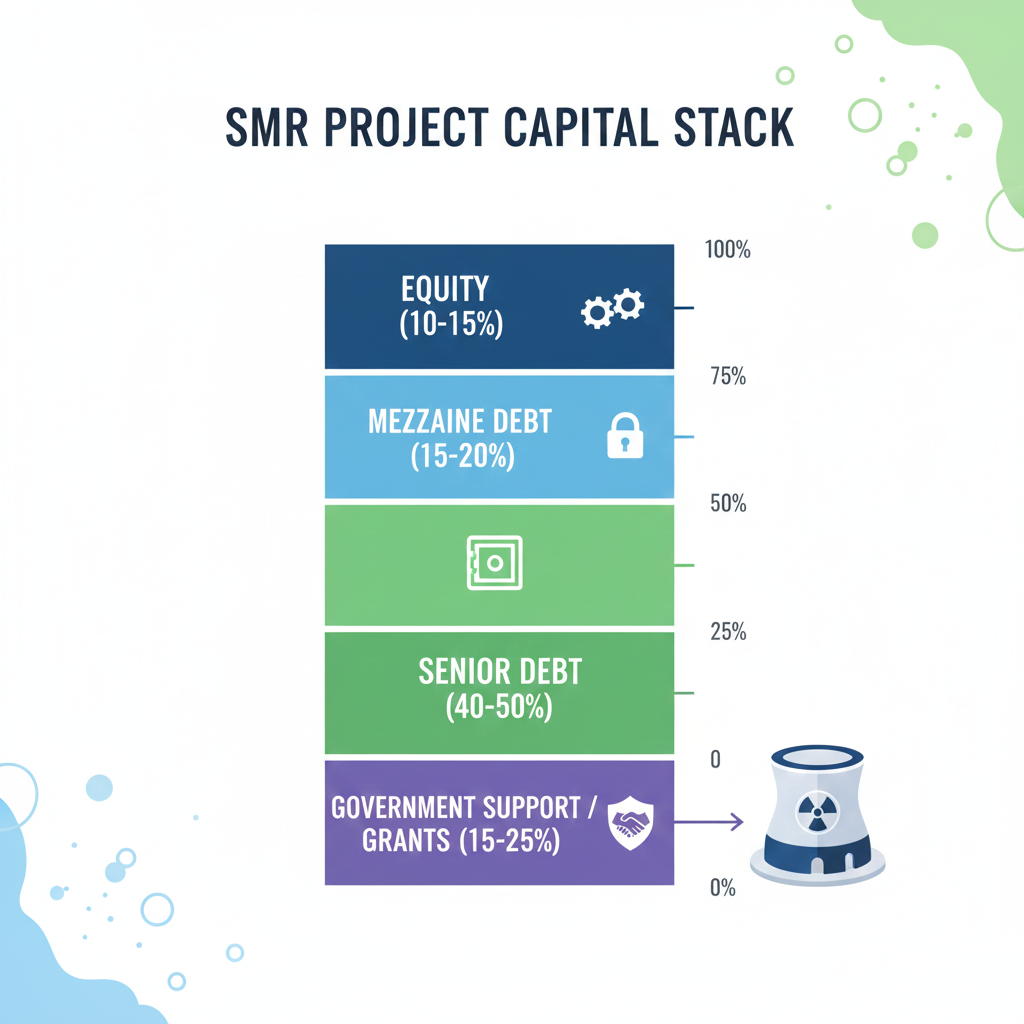

The capital stack: how SMR project finance can actually work

When people say “invest in SMRs,” they often skip the crucial part. Where in the stack?

Project finance is not one thing. It is a negotiated machine. It turns engineering into a cashflow that can be sliced into senior debt, mezzanine debt, tax equity in some contexts, preferred equity, and common equity.

In nuclear, the stack is unusually sensitive to three categories of risk: licensing, construction, and fuel supply. If you misprice those, your return is fantasy.

Senior debt wants discipline, not hype

Traditional project finance lenders look for predictable cashflows, fixed-price EPC contracts, credible completion guarantees, and strong offtake.

SMRs challenge each one.

EPC pricing is hard without repetition. Supply chains are still developing. Regulatory timelines can move. So senior debt often demands more support. That support can come from government programs, utility involvement, or unusually strong sponsor balance sheets.

This is why the early SMR wave is likely to be sponsor-heavy. Balance-sheet capital may lead, with project finance debt scaling later as the industry standardizes.

Offtake is the bridge between “idea” and “asset”

In 2026, the most exciting innovation is not the reactor core. It is the contract.

A corporate buyer can structure an agreement that stabilizes revenue. A utility can provide grid integration and regulatory familiarity. A government can provide a backstop that reduces tail risk.

These combinations are what transform an SMR from a science project into an infrastructure asset class.

RAB and CfD: the financing templates investors keep revisiting

Globally, nuclear financing discussions often return to two models because they shift risk away from fragile merchant revenue.

A regulated asset base model allows certain costs to be recovered through regulated charges, reducing exposure to market prices. A contract for difference model stabilizes revenue by paying the difference between a strike price and market price.

International institutions have documented these as relevant nuclear financing approaches, including how they can function as variations on power purchase structures. (IAEA Publications)

In plain language, these frameworks make it easier to finance long-build assets. They do so by shrinking the revenue uncertainty that scares lenders.

[YouTube Video]: A focused session on getting nuclear financing right. It helps here because it walks through why funding structures matter as much as technology when underwriting 2026 projects.

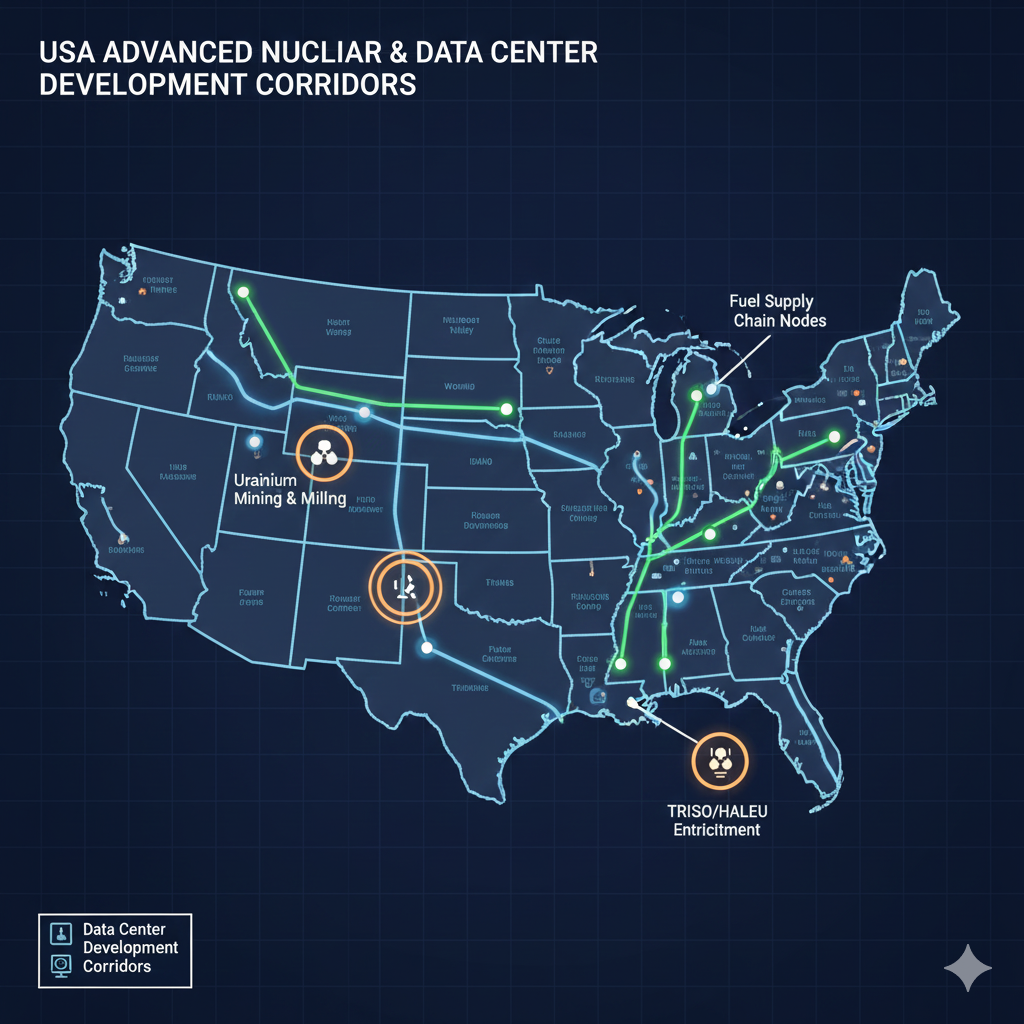

The hidden bottleneck: fuel, supply chains, and the “HALEU clock”

A critical 2026 reality is that advanced reactors can be constrained by fuel availability, not just engineering.

Many advanced designs depend on HALEU, a higher-assay low-enriched uranium fuel category. If fuel delivery is uncertain, timelines become fragile. If timelines become fragile, financing costs spike.

That is why U.S. policy actions around HALEU are being watched closely. In 2025, the U.S. Department of Energy described allocations and steps tied to making HALEU available to the industry. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov)

This is not a niche detail. It is a core underwriting variable for 2026 and beyond.

Why supply chain realism changes returns

Investors love “next-generation” stories. Lenders love repeatable procurement.

Early SMR projects may face higher costs because vendors are still scaling. Specialized components have limited suppliers. Quality standards are strict. As a result, contingency budgets must be honest.

Additionally, construction sequencing matters. Some projects aim to start non-nuclear site work while regulatory reviews continue, which can improve schedule optics but also introduces its own coordination risks. TerraPower has described the logic of moving ahead on non-nuclear portions while NRC review proceeds. (TerraPower)

The data center integration question: grid-tied vs “behind the meter”

The most emotionally appealing idea is simple: put an SMR next to a data center, plug it in, and enjoy stable power.

In practice, integration is nuanced.

Behind the meter: seductive, but complex

Behind-the-meter power can reduce transmission dependence and improve reliability. It also raises tricky issues, including licensing boundaries, safety zones, and the operational interface between a nuclear facility and a private industrial campus.

From a financing view, behind-the-meter structures can be attractive because the offtaker is directly linked. However, they can also concentrate risk. If the data center load shifts, the power asset loses its anchor. If public acceptance becomes a fight, the project becomes political.

Grid-tied: slower, but often more financeable

Grid-tied projects can be easier to permit in established frameworks. They can also sell power more flexibly.

This is why many early deals are framed through PPAs and utility relationships, rather than a pure “private reactor for a private server farm” concept.

The Constellation and Microsoft arrangement is a useful reference point in public discourse because it demonstrates how a corporate buyer can pursue nuclear supply through a structured long-term agreement. (Constellation)

What to expect in 2026: the financing market evolves in three ways

Entering 2026, the SMR financing story is likely to change shape. The most probable evolution is not a sudden flood of fully financed projects. It is a steady tightening of the commercial template.

First, hyperscalers will standardize nuclear procurement playbooks

In renewables, corporate PPAs became a repeatable product. Nuclear procurement is now inching toward a similar professionalization.

Google’s early deal framing with Kairos is important because it signals a willingness to do multi-unit planning rather than a single-off experiment. (Kairos Power) Expect 2026 to bring more master agreements, more structured options, and more negotiation around delivery risk.

Second, the market will reward “boring” structures

The most investable SMR deals in 2026 will not be the most futuristic. They will be the most bankable.

That likely means utility partnerships, regulated recovery mechanisms where available, and government-linked support. International nuclear financing reports have highlighted frameworks like regulated cost recovery and other structured approaches used in past nuclear builds. (Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA))

Third, capital will move into picks-and-shovels exposure

Not every investor needs to own the reactor equity.

Some will prefer exposure through engineering firms, component suppliers, fuel cycle participants, and grid infrastructure upgrades. This approach can feel less glamorous, but it can be rewarding because it reduces single-asset binary risk.

New regulations and policy pressure points that could shape 2026

Policy matters in nuclear more than in almost any other infrastructure category. That is not a complaint. It is the nature of safety-critical systems.

The United States: licensing intent is clear, execution is the test

The NRC’s ADVANCE Act page outlines a set of required actions aimed at improving advanced reactor and fuel licensing processes. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) The underwriting question for 2026 is how those mandates translate into predictable timelines without weakening safety.

Separately, broader public reporting has noted accelerating interest from utilities and policymakers as demand rises, particularly due to data centers. (AP News) Even when political narratives shift, the demand math stays. That keeps pressure on permitting systems.

The United Kingdom: SMR selection adds a global benchmark

In mid-2025, the UK selected Rolls-Royce SMR as a preferred bidder in its SMR competition, pointing toward a structured national pathway for SMR deployment. (Reuters)

For global investors, this matters because it creates a comparable reference case. It also signals that “state-enabled nuclear finance” remains a powerful lever.

Fuel policy: HALEU availability becomes an investing headline

DOE communications about HALEU allocations underline that fuel is being treated as a strategic enabler for advanced reactor timelines. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov) If 2026 brings clearer fuel bank mechanisms and reliable delivery schedules, financing confidence can rise. If not, capital will demand a premium.

A practical due diligence lens for 2026 investors

A clean story is not enough. Nuclear requires relentless diligence.

Start with counterparties. Who is buying the power, and on what terms? Then move to schedule realism. Who owns cost overruns? Who bears delay damages? Additionally, inspect the regulatory pathway with humility. What is the exact licensing track, and what is the credible timeline?

Fuel risk deserves its own line item. If a design needs HALEU, what is the sourcing plan? Is it contractual, or aspirational? DOE’s public positioning on HALEU availability shows progress, but project-specific certainty still varies. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov)

Finally, check governance. Mega-projects fail when decision rights are blurry. They succeed when accountability is sharp.

This is where family offices and infrastructure allocators can add real value. They can demand disciplined reporting. They can insist on contingency transparency. They can refuse magical thinking.

Forecasting 2026 outcomes: three scenarios investors should model

Forecasts are not fortune-telling. They are preparation.

Base case: more deals, but still selective capital

The base case for 2026 is a rise in corporate nuclear contracting activity, plus more public-private financing structures. We should expect more announcements like the ones already seen from major tech buyers, without assuming that every announcement becomes a financed steel-in-the-ground project immediately. (About Amazon)

In this scenario, returns concentrate in teams that can execute and in structures that reduce downside tails.

Upside case: standardization lowers cost of capital

The upside scenario is driven by repetition.

If designs standardize, EPC pricing improves. If licensing becomes more predictable, construction risk premiums shrink. If fuel availability becomes routine, schedule risk falls.

In that world, the cost of capital can compress. That compression is powerful. It can turn “interesting” projects into “obvious” infrastructure allocations.

Downside case: timeline slippage triggers a sentiment reset

The downside scenario is emotional, and therefore dangerous. It is the moment when delays hit headlines, public acceptance sours, and capital retreats.

This scenario has precedent in energy history. Consequently, 2026 investors should stress test for delay, cost inflation, and political friction. Projects can survive these shocks, but only with honest contingency design.

How to prepare for 2026 changes without getting reckless

The winning posture for 2026 is not blind optimism. It is disciplined readiness.

First, treat SMRs as a multi-cycle theme. The fastest wins may come from enabling infrastructure rather than reactor equity. Additionally, focus on counterparties and contracts. The offtake agreement is where value is created and protected.

Second, insist on transparency around licensing milestones. Public timelines can guide expectations, but each project’s path is unique. TerraPower’s stated regulatory tracking into 2026 is one example of how developers communicate milestones, yet execution still needs continuous verification. (TerraPower)

Third, be realistic about liquidity. Private infrastructure deals do not trade like stocks. If you need instant exits, you are in the wrong arena.

Finally, do not confuse “uncorrelated” with “risk-free.” Nuclear can be uncorrelated to equities while still being exposed to execution risk. That risk is manageable, but only with rigorous underwriting.

Conclusion: 2026 is the year nuclear finance gets serious

SMR project finance for AI data centers is moving from cocktail-party speculation into structured competition.

The demand signal is intense. The contracts are emerging. The policy environment is warming. (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) Meanwhile, the bottlenecks are real: fuel, supply chain, and licensing complexity. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov)

That tension creates a rare kind of investing moment. It is both thrilling and unforgiving.

If 2026 becomes the year of “energy security capital,” then the winners will not be the loudest promoters. They will be the calm, proven teams who build financeable structures, price risk with courage, and deliver dependable electrons when the grid is begging for relief.

Sources and References

- Amazon signs agreements for innovative nuclear energy projects

- Google’s nuclear energy agreement with Kairos Power

- Kairos Power: Google agreement to deploy 500 MW

- Constellation: PPA and Crane Clean Energy Center announcement

- World Nuclear News: TMI restart to power Microsoft (report)

- NRC: About the ADVANCE Act

- DOE: HALEU availability program update

- OECD-NEA: Frameworks and strategies for financing nuclear new build (PDF)

- IAEA TECDOC: Financing structures including CfD and RAB (PDF)

- TerraPower: Natrium permit and NRC timeline update

- NRC: TerraPower Kemmerer (Natrium) application page

- Reuters: UK selects Rolls-Royce SMR (report)